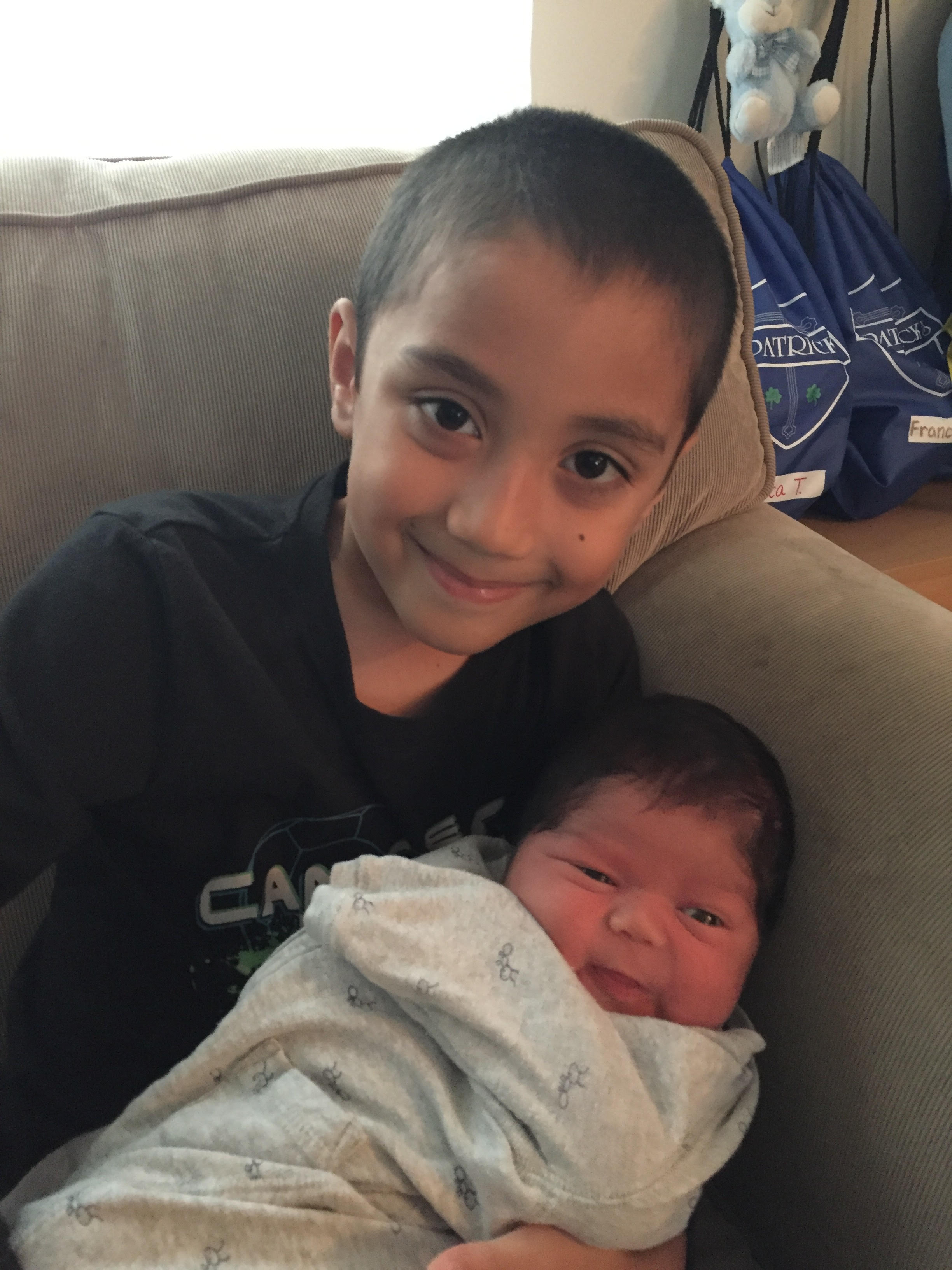

The Heldt Family, minus their latest bundle of joy.

On November 21 of this year, I returned to the University of California, Berkeley, to explain the pro-life view to one hundred students who signed up for the course, “Public Health 198.” I would be presenting after their course’s sponsor teacher, Dr. Malcolm Potts (abortionist and first medical director of International Planned Parenthood Federation) gave his talk on why he believes abortion is right.

Having spoken to hundreds of his students the year prior, I listened to last year’s recording. And when I heard myself, I felt I had relied too much on the intellectual case and not enough on stories that reach the heart. So I began to pray about how I could better package the message this year. Kneeling in one of my favorite chapels in Vancouver, I prayed for inspiration, and sensed that my message should focus primarily on beauty.

Without my notebook, I grabbed the next best thing—notepad on my phone, and began to type ideas. I saw that on that same notepad entry, a couple weeks before while speaking in Guatemala, I had typed a note when I heard another speaker, Clay Olsen; he said, “Make it cool first and inform them second.” That’s what I would do—share stories of beauty, of those who authentically live the pro-life message to show it is possible to do so, and only then segue into pro-life apologetics.

A beautiful family I met several years ago while in Denver came to mind—Brianna Heldt and her husband Kevin (whose story I share below). I jotted that idea down. I wrote, “They need Jesus”—which was a deep conviction I had while speaking to the students a year ago as I sensed a very broken and hostile crowd. I further typed, “Give them Jesus in the faces of the Heldts, Ryan, Lianna.”

In my 14-plus years of travelling the world, I have met the most incredible pro-life people whose inspiring life choices would move you to tears. Having interacted with many hostile abortion supporters I have come to see that my experiences and theirs are very different. They have not met the people I’ve met, not seen the things I’ve seen, not experienced the love I’ve experienced. It is love and beauty that is at the heart of the pro-life message and this time at Berkeley I would introduce them to this other world.

After my opening, I addressed the “tough cases” people often raise to justify abortion. I began with poor prenatal diagnosis and poured out the beauty: I told my story of meeting limbless inspirational speaker Nick Vujicic back in 2010, and spending time with him along with a then-2-year-old girl, Brooke, who was born without arms. I talked about how Nick had contemplated suicide when he was younger, but he eventually realized that instead of focusing on what his disability prevented him from doing, he could focus on what it enabled him to do. As this documentary shows, Nick lives a full and satisfying life, inspiring and motivating people all around the world. I then told them about Brooke: her parents were offered an abortion when a routine ultrasound showed she had no arms. But they rejected that, got connected to Nick, and now Brooke has also learned how to turn an obstacle into an opportunity. Abortion doesn’t have to be the answer; we can choose a better way.

Nick and Brooke’s lived experiences are really about perspective—that we can choose our response to situations we haven’t chosen. So I then shared the story of photographer Rick Guidotti who devotes his time and talent to use “photography, film and narrative to transform public perceptions of people living with genetic, physical, intellectual and behavioral differences.” I played a clip from this documentary featuring him, to illustrate a better response than abortion to poor prenatal diagnosis.

Then I addressed the hard case of rape. Besides playing the trailer of the powerful documentary “Conceived in Rape,” I told the story of my new friend Lianna, a fellow speaker I met in Guatemala. I told the students that Lianna was raped at the age of 12 and became pregnant. I read this portion of an interview with her:

“Lianna asked the doctor if abortion would help her forget the rape and ease her pain and suffering. When he replied ‘No,’ she realized that ending the baby’s life would not really benefit anybody.

“‘If abortion wasn’t going to heal anything, I didn’t see the point,’ she said.

“‘I just knew that I had somebody inside my body. I never thought about who her biological father was. She was my kid. She was inside of me. Just knowing that she needed me, and I needed her…it made me want to work, to get a job [to support her],’ she said.

“Rape caused Lianna’s life to become a living hell. No matter how many times she showered, she could not rid herself of feeling dirty. The idea of suicide seemed to offer the young girl instant release from so much misery, but she began to realize that she had to think not only about herself, but about the future of this little life that was blossoming within her body.”

I further told the students that Lianna says, “I saved my daughter’s life and she saved mine.”

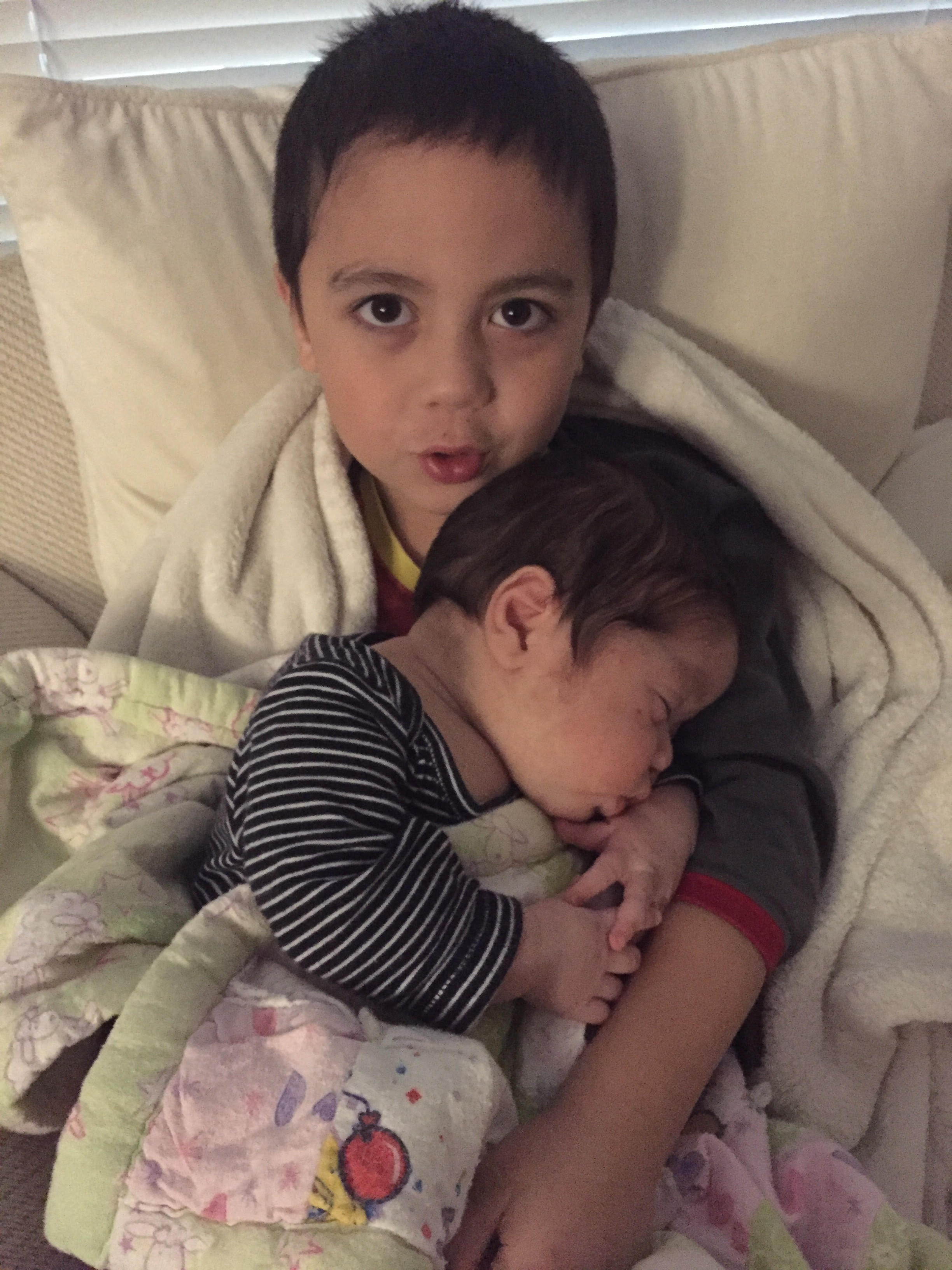

But what if someone feels they can’t parent their child like Lianna did? That brings me back to Brianna and Kevin, the couple I met in Denver a few years ago. I infrequently speak about adoption, and decided to emphasize it in my talk at Berkeley. When the Heldt’s first child was only one year old, they adopted two children. They have since adopted two more children, both of whom have down syndrome and serious heart conditions, along with having 7 more biological kids (but tragically losing 3 of them to miscarriage). Brianna wrote, which I quoted for the students,

“When we adopted my sons, we went from being a family of three to a family of five. As one would expect, we got lot of ‘Why are you doing that?’ and, when I became pregnant four months after my sons joined our family (taking us to a family of six), a lot of ‘Was this an accident?’ And when I answered no, a lot of dumbfounded looks. What struck me most back then (and still does today) is that people were incredulous not so much because of the number of children we had, but simply because we were saying yes. Being open. Allowing love to grow and exponentially multiply, which it always does when a family is graced with new life.

“Those early years of our marriage with four itty-bitty children were outright hilarious, but they were beautiful too. If I could go back for a time, I would. A three-year-old sister sneaking cookies from the pantry to distribute to two-year-old brothers. Sloppy kisses and chubby hands welcoming a new baby sister. Exhausted parents collapsing onto the couch at the day’s end, laughing at how ridiculously amusing our life was.

“But there was love. Always.”

I told the students that “suffering unleashes love” (one of my favourite quotes from St. John Paul II), and that while Dr. Potts is saying that the suffering in the world should unleash violence (i.e., abortion), I would like to propose—not impose, but propose (to borrow the phrase of the late Fr. Richard John Neuhaus who I discovered was simply borrowing more great words from St. John Paul II)—that suffering unleash love. I would like to propose that we follow in the footsteps of people who prove this is possible, people like the Heldt’s, Lianna, Nick, Brooke and her family, and Rick Guidotti.

There is much more that 50 minutes plus Q & A allowed me to share (that a brief blog post does not), but suffice it to say I sought to heed the words of Dostoevsky: “beauty will save the world.”

P.S., The good news? One of the course organizers e-mailed me, “Based on our evals (we run a short iClicker evaluation) students overwhelmingly enjoyed your presentation. Since we didn’t have discussion sections due to the holiday, we weren’t able to get a full idea of their feedback, but students were happy to talk to us after and were very receptive to your message.”